Sea horses are classified in the family Syngnathidae (pronounced sin-NATH-ih-dee). Every animal in this family is a fish. Syngnathdae is Greek for ‘fused jaws’ because the mouths of fish in this family do not open or close. About 330 species of Syngnathidae have been classified. Thirty-seven of these species are sea horses, three are sea dragons (Leafy, Weedy, and Ribboned), and the rest are pipehorses or pipefishes.*

Sea horses are classified in the family Syngnathidae (pronounced sin-NATH-ih-dee). Every animal in this family is a fish. Syngnathdae is Greek for ‘fused jaws’ because the mouths of fish in this family do not open or close. About 330 species of Syngnathidae have been classified. Thirty-seven of these species are sea horses, three are sea dragons (Leafy, Weedy, and Ribboned), and the rest are pipehorses or pipefishes.*

Where do sea horses live?

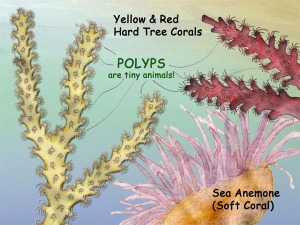

Most sea horses live in shallow ocean water near land. Sea horses may be found in estuaries, mangrove swamps, sea grass meadows, or reefs around the world.

Why do sea horses hide?

Larger fish like tuna or red snapper eat sea horses. Sea turtles, sting rays, sharks and even penguins munch on sea horses, too. Sea horses hide from these predators by changing color to match their environment.

How do sea horses move?

Sea horses move slowly by means of fins that beat as fast as 70 times per second! The dorsal fin propels the sea horse forwards. Sea horses have two, small pectoral fins (one behind each gill) that allow the sea horse to hover or change direction.

What do sea horses eat?

Sea horses do not have teeth, so they swallow their food whole. Sea horses suck food into their long, narrow snout, but the food must be tiny to fit through their mouth. Sea horses eat zooplankton, little shrimp, and the larvae of fish, crab, or worms. Sea horses do not have stomachs either. Without a stomach, sea horses cannot digest food well, so they have to eat large amounts in order to survive. Sea horses may eat for up to 10 hours per day, and they may swallow 50 to 300 tiny animals per hour!

What is the largest sea horse?

The Big-Bellied Sea Horse (Hippocampus abdominalis) is the largest species. These sea horses may reach fourteen inches in length!

What is the smallest sea horse?

Hippocampus denise is a pygmy sea horse that measures about half an inch in length.

More About Sea Horses…

Sea Horse Diagram for the Classroom

Draw and Color a Sea Horse with a Dot-to-Dot Activity

*My Favorite References…

Seahorses, Pipefishes and Their Relatives: A Comprehensive Guide to Syngnathiformes.

Author Rudie H. Kuiter. TMC Publishing, Chorleywood, UK. Revised 2003.

Poseidon’s Steed: The Story of Seahorses, From Myth to Reality.

Author Helen Scales, Ph.D. Gothan Books, New York, NY, USA. ©2009.

Project Seahorse.

Author Pamela S. Turner. Houghton Mifflin Books for Children, New York, NY, USA. ©2010.